The Salisbury National Cemetery is not far from Main Street. The grass is impeccably mowed, and beyond the strong iron gate, the headstones are clean and standing in precise lines—rows and rows of them—many decorated with American flags. It is the resting place of 11,700 Union Soldiers who died at Salisbury Prison during the Civil War.

Turn your gaze a little to the left, just past a local community center, and you’ll see another burial ground located just over a quarter of a mile away. That’s Dixonville, one of the area’s oldest African American cemeteries. It is barely more than a grassy knoll, and even though there are almost 500 documented burials here, there are only about twenty-eight headstones standing.

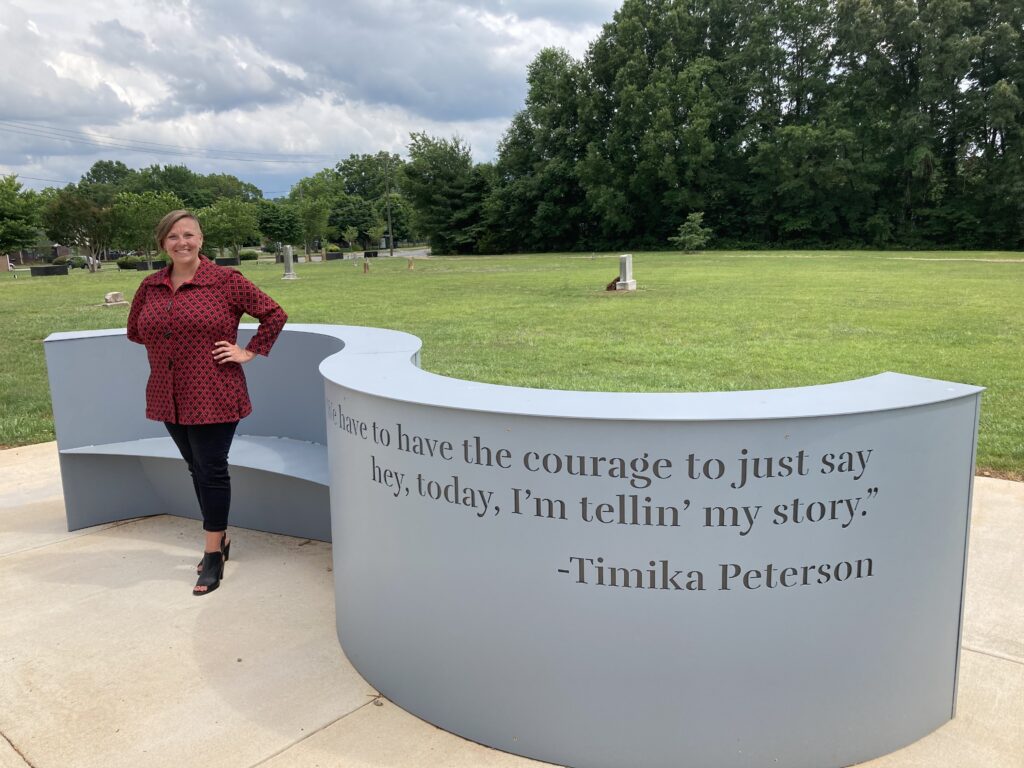

Bailey Wingler (’18 BFA Art) decided that Dixonville is one of many stories that needed to be told. Wingler is the grant project assistant for Rowan-Cabarrus Community College (RCCC) and is managing “Here’s My Story,” a project funded by the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation. She works with Jenn Selby, Director of Philanthropy, Transfers, and the Arts at RCCC.

Selby says: “When conversations were being held about confederate monuments, the Reynolds Foundation put out a call for public art projects focused on giving historically marginalized people a voice through art. They awarded $100,000 toward ten projects in North Carolina, and Rowan-Cabarrus was the only community college funded. Bailey has taken this project and run with it.”

“Here’s My Story” was developed by the sculpture faculty at RCCC’s Fine Arts Department. Three benches with speakers at shoulder height allow visitors to hear local residents tell stories of challenges. The S-shape of the benches makes them wheelchair accessible. Each bench has a QR code that connects to youtube recordings with closed captioning for the hearing impaired. The stories are about ten minutes in length with four stories running in a loop at each location. One of the benches has been installed at RCCC’s North Campus, another at Dixonville Cemetery, and a third location is yet to be determined.

Wingler is responsible for soliciting the stories, interviewing participants, and editing them:

“We did a lot of community engagement. We put out flyers and we went to local high school football games, posted on social media, and put up information at the YMCA. The response was amazing. People came to us and said I consider myself a marginalized person, let me tell my story. Some people walk in with a specific story they want to share, and I just hit ‘record’ and let them say what they have to say. Others will come in not sure what to talk about, so we do prompts to get the ball rolling. I was thrilled to get some stories about Dixonville Cemetery. I love that people can sit on that bench and listen to the stories while looking out on that site.”

One of the recordings is a memory of Dixonville Cemetery as a pathway that the children of Dixonville traveled to and from Lincoln School. The School, formerly known as the Colored Graded School, was established in the late 1800s and was the first Black public school in Salisbury:

“We had to walk through this cemetery to get to school. There was a big ol’ pear tree and a pecan tree, and we would stop and eat our fill of pecans and everything. I have good memories about this cemetery.”

Wingler works with an advisory committee to select the stories:

“The goal of the project is to show how diversity makes a community better. How it makes us stronger, more resilient, so we’re looking for stories that are reflective of that. If a story doesn’t go on a bench, it’s still archived at the library so it can be shared that way. The project has created a real sense of community. So many of our storytellers have stayed in touch. This project has changed me completely, and I hope it will change our community for the better.”

Wingler says she never anticipated her degree at UNCG would lead her to this job, but she was ready for it:

“The School of Art prepared me for this project by fostering a creative mindset and the ability to be open to new possibilities and to be aware of what’s happening in the world. My experience at UNCG taught me how to take things that are important to me and to explore them in a creative way. It also taught me that I could do anything if I just worked at it. I was going to college with two young children. I drove them to school in Salisbury then went to Greensboro for my classes then back to Salisbury to pick up my kids. Having professors who understood what it meant to have a family was important.”

Wingler and Selby hope what is a community-based initiative will become a state-wide project. As the grant is starting to wind down, they’re exploring the possibility of developing a separate non-profit to keep “Here’s My Story” going:

“It’s been such a personal experience. And it’s exciting to see something that’s more than a sculpture. Sculpture is beautiful, but this is something that the community is so engaged in and that the community owns. This experience has allowed me to combine my art background and an element of service. That is very powerful to me.”

Stay tuned: PBS is doing a documentary about some of the Z. Smith Reynolds funded projects, including “Here’s My Story.” The segment on the talking benches was shot in June of 2021, but production on other projects was delayed due to COVID, so the documentary will not air until all of the projects are completed.

“Here’s My Story” will also live on in print. Wingler is working on a book highlighting aspects of the project and the significance of the sites, and it will include portraits of many of the storytellers. Wingler says there is also interest in expanding the project into surrounding counties, and she’s working on plans to train others how to facilitate similar projects in other communities.

Story and Photo by Terri W. Relos